Inflation accelerates as companies stock up in anticipation of surge in demand

09/27/2021 / By Nolan Barton

Companies are trying to stock up in anticipation of a huge surge in demand as the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic worsens anticipated shortages.

From mattress producers to car manufacturers to aluminum foil makers – they are all buying more material than they need. Shortages, transportation bottlenecks and price spikes are nearing the highest levels in recent memory.

“You bring all of these factors in, and it’s an environment that’s ripe for significant inflation, with limited levers for monetary authorities to pull,” said David Landau, chief product officer at BluJay Solutions, a U.K.-based logistics software and services provider. (Related: Get ready for the most painful inflation since the Jimmy Carter years of the 1970s.)

However, policymakers have laid out a number of reasons why they don’t expect inflationary pressures to get out of hand.

They say that the big surges lately are partly blamed on skewed comparisons to the steep drops of a year ago and many companies that have held the line on price hikes for years remain reticent about them now. U.S. retail sales also stalled in April after a sharp rise in the month earlier and commodities prices have recently retreated from multi-year highs.

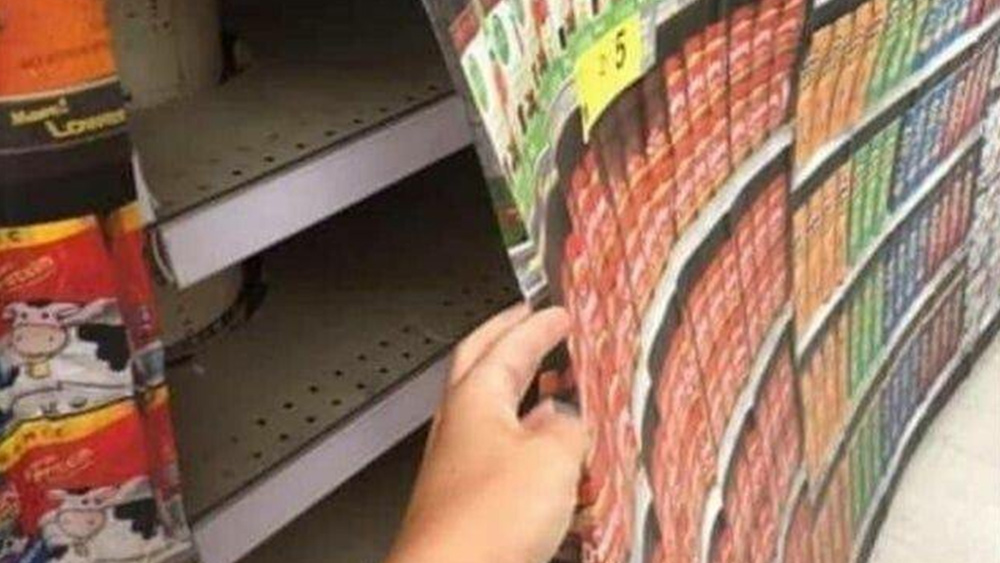

Companies are trying to hoard what they can

Dennis Wolkin’s family has been making crib mattresses for three generations. Economic expansions are usually good for baby bed sales, but the extra demand means little without the key ingredient: foam padding. There’s a shortage of polyurethane foam that Wolkin uses because companies are over-ordering and trying to hoard what they can.

“It’s gotten out of control, especially in the past month,” said Wolkin, vice president of operations at Atlanta-based Colgate Mattress, a 35-employee company that sells products at Target stores and independent retailers. “We’ve never seen anything like this.”

Though polyurethane foam is 50 percent more expensive than before the COVID-19 pandemic, Wolkin would buy twice the amount he needs and look for warehouse space rather than reject orders from new customers. “Every company like us is going to overbuy,” he said.

Even multinational companies are just trying to cope. Whirlpool Corp. CEO Marc Bitzer told Bloomberg Television this month that its supply chain is “pretty much upside down,” and the appliance maker is phasing in price increases.

Whirlpool and other large manufacturers normally produce goods based on incoming orders and forecasts for those sales. Now they are producing based on what parts are available.

“It is anything but efficient or normal, but that is how you have to run it right now,” Bitzer said. “I know there’s talk of a temporary blip, but we do see this elevated for a sustained period.”

Running low on everything

The world is seemingly low on everything: copper, iron ore, steel, corn, coffee, wheat, soybeans, lumber, semiconductors, plastic, cardboard for packaging, etc.

“You name it, and we have a shortage on it,” said Tom Linebarger, chairman and chief executive of engine and generator manufacturer Cummins Inc.

Girteka Logistics, Europe’s largest fleet of trucks, is struggling to find enough capacity. Monster Beverage Corp. of Corona, California, is dealing with an aluminum can scarcity. Hong Kong’s MOMAX Technology Ltd. is delaying the production of a new product because of a shortage of semiconductors.

The semiconductor shortage has already spread from the automotive sector to Asia’s highly complex supply chains for smartphones.

“The semiconductor shortage will severely disrupt the supply chain and will constrain the production of many electronic equipment types in 2021,” Kanishka Chauhan, principal research analyst at Gartner said in a mid-May report on the situation. “Foundries are increasing wafer prices, and in turn, chip companies are increasing device prices.”

The shortage is expected to cost the global automotive industry $110 billion in revenue in 2021.

Calamities make everything worse

Calamities, man-made and otherwise, have exacerbated the situation.

A freak accident in the Suez Canal backed up global shipping in March. Drought has wreaked havoc upon crops. A deep freeze and mass blackout wiped out energy and petrochemicals operations across the central U.S. in February. Less than two weeks ago, hackers brought down the largest fuel pipeline in the U.S., driving gasoline prices above $3 a gallon for the first time since 2014. India’s massive COVID-19 outbreak rocked the shipping industry.

Problems may persist because the capacity to produce more of what’s scarce is slow and expensive to ramp up. Prices of lumber, copper, iron ore and steel have all surged in recent months as supplies constrict in the face of stronger demand from the U.S. and China, the world’s two largest economies. (Related: Supply shortages are leading to price hikes, worsening inflation.)

Crude oil is also on the rise, as are the prices of industrial materials from plastics to rubber and chemicals. Some of the increases are already making their way to the store shelf. Reynolds Consumer Products Inc., the maker of the namesake aluminum foil and Hefty trash bags, is planning another round of price increases – its third in 2021 alone.

Food costs are climbing, too. The world’s most consumed edible oil, processed from the fruit of oil palm trees, has jumped by more than 135 percent in the past year. Soybeans topped $16 a bushel for the first time since 2012. Corn futures hit an eight-year high while wheat futures rose to the highest since 2013.

A United Nations gauge of world food costs climbed for an 11th month in April, extending its gain to the highest in seven years.

Follow Pandemic.news for more news and information related to the coronavirus pandemic.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: agricultural crops, automotive industry, chaos, Collapse, coronavirus, covid-19, covid-19 pandemic, crude oil, edible oil, Inflation, pandemic, petrochemicals, price increases, supply chain, supply lines

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 FOOD COLLAPSE