Surge in shipping costs, bottlenecks at ports threaten global economic recovery

08/19/2021 / By Nolan Barton

The price of moving a 40-foot container from China to the West Coast has jumped to almost $16,000 – a tenfold increase from pre-pandemic costs – as surging shipping prices and bottlenecks at ports threaten global recovery from the economic crisis inflicted by the Wuhan coronavirus (COVID-19).

From Shanghai to Rotterdam, transporting a 40-foot steel cargo container by sea now costs a record $10,522 – 547 percent higher than the seasonal average over the last five years.

“I think it’s the single biggest threat the economy faces at the moment. It’s only just starting to bite. Imagine if oil went up from $20 per barrel to $200 per barrel, then that would be tantamount to what’s happening now,” a person working for a U.K. freight company said.

Both importers and exporters share that view as soaring shipping costs throw global supply chains into turmoil.

The rise in costs and delays at ports made worse by COVID-based closures of key Chinese facilities have added to existing problems, such as the global semiconductor shortage and rising prices of raw materials. Supply chain pressures are already starting to show up in macroeconomic statistics. They were noticeable in weak industrial production figures over the summer in Europe.

Meanwhile, ports are facing their biggest crisis since the start of container shipping 65 years ago, as hundreds of vessels are lined up outside terminals waiting to dock. (Related: COVID-era freight demand has NOT surged at all, so why all the congestion, delays and shocking freight price increases?)

Operators are already under pressure to upgrade their facilities with bigger cranes and deeper docks to cater to the new generation of super ships and adapt to changes in consumer behavior such as the demand for next-day deliveries.

Financial Times columnist Claire Jones said it can be difficult to assess how much of the surge in shipping costs is due to demand-led factors and how much is due to the supply side. She also noted that remedies such as building more ships will take years to have any effect.

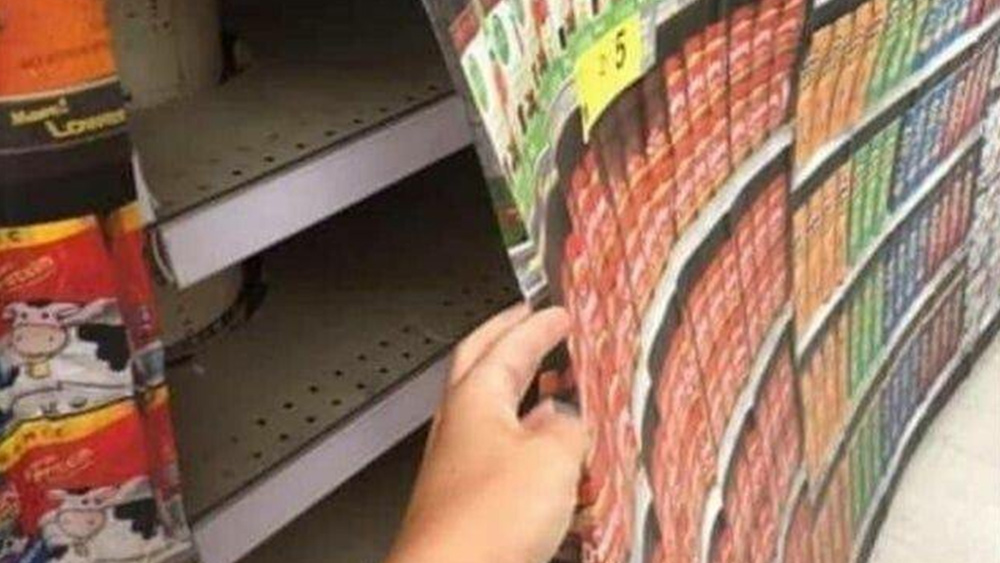

Freight-cost surges threaten to boost product prices

With upwards of 80 percent of all goods trade transported by sea, freight-cost surges are threatening to boost the price of everything from toys, furniture and car parts to coffee, sugar and anchovies. (Related: US companies continue increasing prices of their products, fueling record levels of inflation.)

“In 40 years in toy retailing I have never known such challenging conditions from the point of view of pricing,” said Gary Grant, the founder and executive chairman of the UK toy shop The Entertainer. He has had to stop importing giant teddy bears from China because their retail price would have had to double to add in higher freight costs. “Will this have an impact on retail prices? My answer has to be yes.”

A confluence of factors has contributed to the squeeze on transportation capacity on every freight path, including soaring demand, a shortage of containers, saturated ports and too few ships and dock workers. Recent COVID-19 outbreaks in Asian export hubs like China have made matters worse.

Often dismissed as having an insignificant impact on inflation because they were a tiny part of the overall expense, rising shipping costs are now forcing some economists to pay them a bit more attention. Although still seen as a relatively minor input, HSBC Holdings Plc estimates that a 205 percent increase in container shipping costs over the past year could raise Euro-area producer prices by as much as 2 percent.

At the retail level, vendors are faced with three choices: halt trade, raise prices or absorb the cost to pass it on later. According to Jordi Espin, strategic relations manager at the European Shippers’ Council, all of those would effectively mean more expensive goods. “These costs are already being passed to consumers,” he said.

Prices for customers are rising in other ways, too. For instance, anchovies from Peru have largely stopped being imported into Europe because higher freight costs were not competitive relative to what’s available locally. Also, European olive growers can no longer afford to export to the US.

Shipping bottlenecks and costs are hurting the transport of arabica coffee beans, favored by Starbucks, and robusta beans used to make instant coffee, which are largely sourced from Asia.

For some lower-value furniture makers, freight now makes up about 62 percent of the retail value of their products. “You simply can’t survive on this. Someone is bleeding very hard,” said Alan Murphy, CEO of consultant Sea-Intelligence in Copenhagen

Companies try to work around higher freight costs

Companies are desperately trying to work around the higher freight costs. Some have stopped exporting to certain locations while others are looking for goods or raw materials from nearer locations.

“The longer these extreme shipping freight rates last, the more companies will take structural measures to shorten their supply chains,” said Philip Damas, founder and operational head of Drewry Supply Chain Advisors, the global market leader in sea freight market intelligence and benchmarking. “Few companies can absorb a 15 percent increase in total delivered costs for internationally traded products.”

Central bankers say the rise in consumer prices tied to supply hiccups won’t last. European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde said that while supply-chain bottlenecks would push up production prices and the inflation rate is expected to rise further in the second half of this year, the effect will fade.

Several factors explain the relative lack of concern. Shipping costs only constitute a small fraction of the final price of a manufactured good, with economists at Goldman Sachs Group, Inc. estimating in March – when China-Europe rates were about half of current levels – that internationally they made up less than 1 percent.

Companies also have annual contracts with the container lines, so the prices they’ve locked in are considerably lower than the spot rates.

Many economists note that even a full pass-through of higher shipping fares to consumers will have a marginal effect on headline inflation. But Volker Wieland, a professor of economics at the Goethe University in Frankfurt and a member of the German government’s council of economic advisers, warned that they might not be sufficiently factored in.

“Even if the order of magnitude is smaller than estimated, the dynamic builds over a year and has significant effects,” he said. “That means there’s a danger we’re underestimating the impact.”

Follow Bubble.news for more news related to the economy.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: benchmarking, bubble, Collapse, container shipping, covid-19, economic recovery, food supply, freight company, Inflation, pandemic, shipping bottlenecks, shipping costs, supply chain

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 FOOD COLLAPSE