Indigenous communities are tackling food security and protecting the environment by saving seeds

04/23/2021 / By Divina Ramirez

The Wuhan coronavirus pandemic has upended the global food supply chain, revealing a fragile global food system strained in large part by agrochemical companies’ privatization of seeds. But at the same time, it’s also showed how seed banks can help combat hunger in times of crisis. Indigenous seed banks, in particular, may have a key role to play in addressing global food security.

In Guatemala, the agricultural development nongovernmental organization Qachuu Aloom helps farmers from across the territory of the Maya Achi indigenous group. In addition to helping them get better at traditional and agroecological farming practices, they’re also helping them preserving their native seeds.

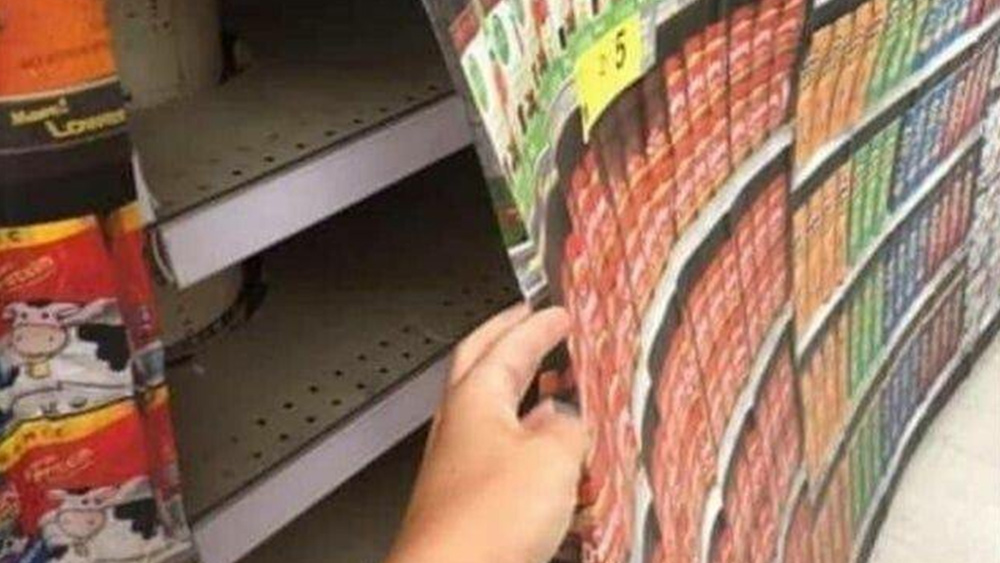

The organization, which has 500 active members, has even built its own seed bank for storing seeds. The bank, more a simple room than an actual seed bank, is filled with floor-to-ceiling shelves of earthenware jars containing seeds from indigenous families across Guatemala.

The seed bank also contains seeds of crops lost during the nation’s decades-long civil war. But the organization does more than save seeds. It has also taken on a diplomatic role, encouraging students and supporters to plant native seeds from the bank across the United States.

Indigenous seed banks can help strengthen global food system

According to Rosalia Cho, coordinator of Qachuu Aloom, indigenous communities around the world have been pioneers in preserving seeds of traditional agricultural crops. Those same communities are also the ones responsible for putting back native seeds and traditional crop varieties into the agricultural scene.

Cho said their work began in 2003 when families started gathering and saving their seeds at home. But a lot of families did not have seeds from plants native to the region, having lost those during Guatemala’s civil war. Hybrid seeds introduced by agrochemical companies also eventually replaced any remaining native seeds.

Last February, the Cherokee Nation, an autonomous tribal government in the U.S., also became the first indigenous nation in the country to deposit traditional seeds in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway. The vault houses roughly a million packets of seeds, each a variety of an important food crop.

Pat Gwin, the Cherokee Nation’s senior director of environmental resources, said the tribe has worked for over a decade finding and cultivating crops they lost when they were forced to relocate to Oklahoma from the southeastern U.S. in the 1830s.

Gwin said the tribes took just one crop with them during the move because it did not feel right to uproot native plants. In other words, the Cherokee Nation started at zero. But that all paid off. The tribe’s own seed bank now has over 100 kinds of seeds. In 2020, the tribe also distributed close to 10,000 packets of seeds to farmers across the U.S.

Experts argue that seeds of traditional agricultural crops, called landraces or heirloom breeds, could help solve food shortages by promoting biodiversity.

The loss of crop biodiversity in commercial agriculture is a pressing problem today. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, approximately three-quarters of the world’s crop genetic diversity has been lost as farmers turned to high-yielding breeds with little genetic diversity. In fact, 95 percent of the energy humans get from food today comes from only about 30 kinds of crops.

Crop biodiversity is fundamental to agricultural growth because it enables farmers to develop varieties that are more productive, with characteristics beneficial for farmers and attractive to consumers. The loss of crop biodiversity means a growing global population depends on a dwindling number of crop varieties.

By saving native seeds and reintroducing them to farmers, indigenous seed banks like the one by Qachuu Aloom and the Cherokee Nation may help strengthen the global food system.

Indigenous seed banks may help address malnutrition

More than just promoting crop biodiversity, indigenous seed banks may also help improve global food security. Nora Castaneda-Alvarez, project manager of the Seeds for Resilience project of the international nongovernmental organization Crop Trust, said seed banks conserve many crops relevant to food security.

Traditional agricultural crops stored in indigenous seed banks are also more nutritious than conventional ones, said Castaneda-Alvarez. Previous studies have shown this to be true in crops like eggplants and chickpeas.

Cho concurs, explaining that the native seeds they carry in their seed bank are nutritious because they came from fertile lands inhabited by the Maya Achi people in the northern region of Guatemala. Cho believes that their ancestral seeds can, therefore, help prevent malnutrition in both children and adults.

Researchers are also now using heirloom breeds from indigenous seed banks in breeding programs to improve the nutritional profile of several food crops. (Related: Cheaper seeds and better-tasting vegetables: Why you need heirloom seeds for your homestead.)

Go to FoodFreedom.news to learn more about seed banks and their role in promoting global food security.

Sources include:

Tagged Under: agriculture, conservation, crop biodiversity, food independence, food supply, indigenous seed banks, seed banks, sustainable living

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 FOOD COLLAPSE